News

Democrats say they’ll avoid election challenges on Jan. 6

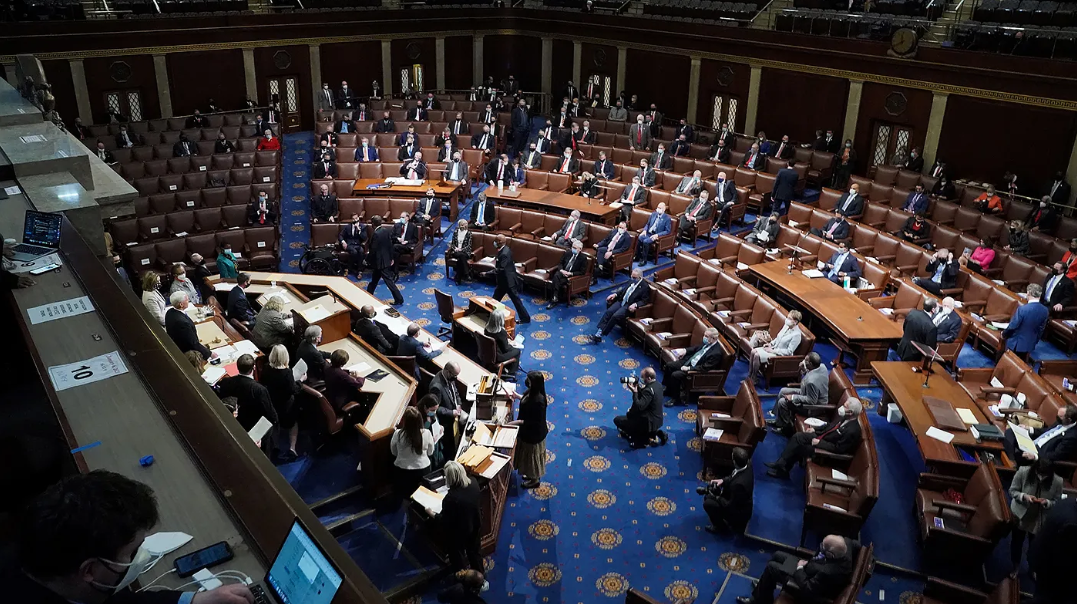

House Democrats say that they’ll skip the election protests they’ve staged on Jan. 6 in past presidential cycles, four years after supporters of President-elect Trump stormed the Capitol in an attempt to interrupt the certification of the 2020 election results.

Democrats typically have used the formal certification of GOP presidential wins to air objections to how certain states carried out their elections.

But they’re treading much more carefully this year after four years in which they’ve accused Trump of directing his supporters to the Capitol for the explicit purpose of overturning President Biden’s victory.

As Jan. 6 nears, and Republicans prepare to certify Trump’s win over Vice President Harris, the last thing Democrats want to do is open themselves to charges of hypocrisy on what they see as a fundamental rite of preserving democracy.

“I don’t know of anybody that wants to do anything that’s going to make it look like we’re somehow questioning the election,” said Rep. Marc Veasey (D-Texas).

Democrats have protested election results in every cycle when a Republican won the White House for at least two decades, so the lack of protests will be a real change.

These past objections have always been symbolic, designed to highlight restrictive election laws or alleged violations of the Electoral College process in specific states.

They have come after the Democratic presidential candidate had already conceded defeat, with no chance — and no intent — of overturning the election results.

For those reasons, the Democrats fundamentally reject the comparison between their own objections and what happened on Jan. 6, 2021, when a mob of Trump supporters, summoned to Washington by the then-president and egged on by his false claims of a “stolen” election, attacked law enforcement officers while storming the Capitol.

Later that night, a majority of House Republicans — 139 lawmakers — voted to overturn Trump’s defeat in Arizona, Pennsylvania or both.

Trump after his inauguration on Jan. 20 may pardon some or many of those convicted of facing crimes from Jan. 6, 2021 — something Democrats say would be a gross miscarriage of justice.

But after spending four years accusing Trump of being directly responsible for the violence, Democrats acknowledge the optics of even symbolic protests might be politically toxic.

Many lawmakers said they don’t want to stage any public objections to the Electoral College results that could create even the slightest appearance — and spark GOP accusations — that Democrats were seeking to invalidate Trump’s victory.

“I don’t want us to do anything to compare to Jan. 6, because nothing will ever compare to what happened on that day,” said Rep. Joyce Beatty (D-Ohio). “Jan. 6 was so surreal and painful and scary, that I don’t think there’s anything that we would do that would want to make us be like them.”

It’s not that Democrats think there were no partisan hijinks that affected election outcomes this cycle. The party is up in arms, for instance, over a new map in North Carolina, drawn by statehouse Republicans, that shifted power heavily in favor of the GOP. As a result, the 14-member House delegation — currently split evenly, at seven seats for each party — will feature 10 Republicans and only four Democrats in the next Congress.

Beatty, a former head of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC), said Democrats will continue to protest such partisan gerrymandering, to include speeches on the House floor. But no one, she said, is going to challenge the outcome of the presidential contest on Jan. 6, particularly because Vice President Harris — who quickly conceded to Trump after her defeat last month — will be presiding over the election certification that day.

“Knowing she’s going to be in the chair, knowing she’s conceded, I wouldn’t go to the floor and say, ‘We didn’t lose the presidential election.’ I mean, duh,” Beatty said. “They may have done that before. But what you would hear would not be a protest against the election results, as they did, you would hear a protest against processes [and] violations of law. So now that may very well happen, but it would not be a denial of the election.”

The caution comes after a number of election cycles when Democrats made a public display of protesting various election procedures in a number of states by challenging the Electoral College results on Jan. 6.

In 2001, for instance, members of the Congressional Black Caucus challenged Florida’s electoral votes to protest the Supreme Court’s decision to halt the recount there — a ruling they said disenfranchised minority voters in the Sunshine State. Then-Vice President Al Gore, who lost that election to George W. Bush, was presiding over the process and gaveled each objection down, one by one.

In 2005, the CBC again led the charge against the electoral count in Ohio, where liberals objected to voting rules they said suppressed the minority vote. That challenge, led by then-Rep. Stephanie Tubbs Jones (D-Ohio), was endorsed by then-Sen. Barbara Boxer (D-Calif.), delaying the process while each chamber debated Ohio’s election laws.

Boxer, at the time, emphasized she was not trying to overturn Bush’s victory over then-Sen. John Kerry (D-Mass.), but she simply wanted to put a spotlight on voting practices she deemed unjust. Her support for the objection forced a vote on the floor of each chamber. In the House, 31 Democrats voted to block the counting of Ohio’s 17 electoral votes.

Rep. Bennie Thompson (D-Miss.), who led the select House committee that investigated the Jan. 6 rampage and Trump’s role in it, was among those 31 lawmakers. This time around, he says he has no plans to protest — a recognition of the violence of 2021.

“I think Democrats recognize, when you lose an election you can either stand on the loss or you can be a bad sport,” Thompson said. “In this instance, I think Democrats want to be the adults in the room and say, ‘Now, Republicans, when this comes around again, look at how we did it.’”

Most recently, a number of Democrats stood to challenge the electoral count in 2017, following Trump’s first victory. That list included Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.), who objected to Alabama’s electoral count citing Russian interference in the election and alleged violations of the Voting Rights Act.

This time, he’s not planning a similar protest.

“I don’t plan to do anything,” he said. “I don’t question the results of this election. I’m heartbroken by the results, but I don’t question them.”

Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-Fla.), a former law professor, had challenged Florida’s tally in 2017 because, he argued, almost a third of Florida’s 29 electoral votes “were cast by electors not lawfully certified because they violated Florida’s prohibition against dual office holding.”

His vote — and all of the Democratic objections over the years — have led Republicans to argue that their efforts to keep Trump in office after his 2020 loss were simply taking a page from the Democratic playbook.

Democrats have rejected those claims outright. And Raskin, like other Democrats, is quick to argue the difference between point-of-order objections like his, and the effort by Republicans to deny an election outcome that Trump still denies even four years later.

“Republicans and Democrats for a long time have used that process to point out flaws in the casting of particular electoral college votes,” he said. “But that is galaxies away from actually trying to overthrow the election with fraud and violence.

“And they know the difference.”