Healthy

Influencers selling fake cures for polycystic ovary syndrome

For 12 years Sophie had been experiencing painful periods, weight gain, depression and fatigue.

She had been diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a hormonal condition that affects about one in 10 women, but she struggled to get medical help.

She felt her only option was to take her health into her own hands, and it was at this moment that Kourtney Simmang came up on her recommended page on Instagram.

Kourtney promised to treat the “root cause” of PCOS, even though researchers have not yet identified one. She offered customers laboratory tests, a “health protocol”- a diet and supplement plan – and coaching for $3,600 (£2,800). Sophie signed up, paying hundreds of dollars more for supplements through Kourtney’s affiliate links.

Dr Jen Gunter, a gynaecologist and women’s health educator, said Kourtney wasn’t qualified to order the tests she was selling, and that they had limited clinical use.

After nearly a year Sophie’s symptoms hadn’t improved, so she gave up Kourtney’s cure.

“I left the programme with a worse relationship to my body and food, [feeling] that I didn’t have the capacity to improve my PCOS,” she said.

Kourtney did not respond to requests for comment.

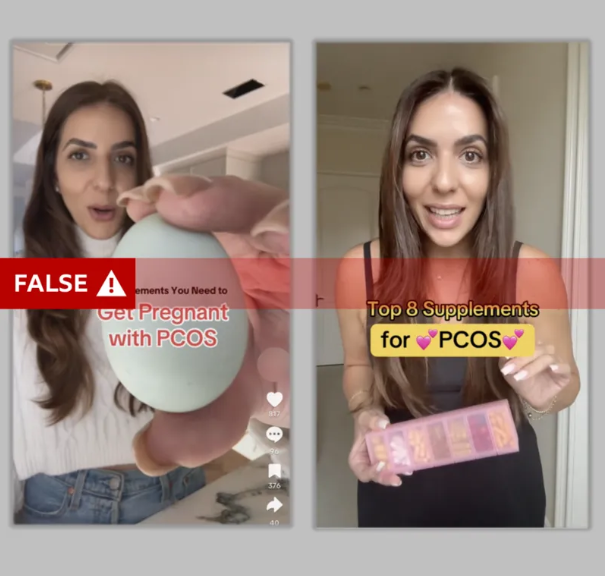

Medically unqualified influencers – many with more than a million followers – are exploiting the absence of an easy medical solution for PCOS by posing as experts and selling fake cures.

Some describe themselves as nutritionists or “hormone coaches”, but these accreditations can be done online in a matter of weeks.

The BBC World Service tracked the most-watched videos with a “PCOS” hashtag on TikTok and Instagram during the month of September and found that half of them spread false information.

Up to 70% of women with PCOS worldwide have not been diagnosed, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), and even when diagnosed, women struggle to find treatments that work.

“Whenever there’s a gap in medicine, predators take advantage,” said Dr Gunter.

The main false or misleading claims shared by these influencers include:

- PCOS can be cured with dietary supplements

- PCOS can be cured with a diet, such as the low-carbohydrate high-fat keto diet

- Birth control pills cause PCOS or worsen symptoms

- Mainstream medication may suppress PCOS, but doesn’t address its “root cause”

There is no evidence that highly restricted calorie diets have any positive effect, and the keto diet may make symptoms worse. Birth control pills do not cause PCOS and in fact help many women, though they don’t work for everyone. There is no known root cause for PCOS and there is no cure.

A spokesperson for TikTok said the company does not allow misleading or false content on the platform that may cause significant harm.

A spokesperson for Meta said user content on women’s health is allowed on the platform with “no restrictions”. The company said it consulted with third parties to debunk health misinformation.

What is PCOS?

- PCOS is a chronic hormonal condition that affects an estimated 8-13% of women, according to the WHO

- The NHS says symptoms include painful irregular periods, excessive hair growth and weight gain

- PCOS is one of the most common causes of infertility, the NHS says, but most women can get pregnant with treatment

They spoke to 14 women from Kenya, Nigeria, Brazil, the UK, the US, and Australia who tried different products promoted by influencers.

Nearly all mentioned Tallene Hacatoryan who has more than two million followers across TikTok and Instagram.

A registered dietician, Tallene sells supplements at $219 (£172) and access to her weight loss app for $29 (£23) a month. She warns people against pharmaceuticals such as the birth control pill, or the diabetes drug, metformin, both of which have been found to be helpful for many women with PCOS.

Instead she encourages her audience to heal “naturally”, with her supplements. She puts a lot of emphasis on weight and what she calls “PCOS belly”, referring to fat around the abdomen.

Amy from Northern Ireland, decided to follow some of Tallene’s advice after struggling to get help through her GP.

“PCOS belly was exactly where my insecurities were,” she told me.

Tallene’s advice is to reduce gluten and dairy, and to follow the keto diet. But while a healthy diet can help with PCOS symptoms there is no evidence that gluten and dairy have a negative effect.

In Amy’s case, the keto diet regularly made her sick, and she found it hard to cut out gluten and dairy products.

“It makes you feel like you failed,” she said. “Looking back, I wasn’t as heavy then, but these people would make me feel worse, and you’d want to do more diets, or buy more supplements.”

Dr Gunter told the BBC influencer diet plans such as these could “absolutely create an eating disorder”.

Tallene did not respond to the BBC’s request for comment.

Amy said her GP had offered her hormonal birth control to manage her symptoms, but didn’t have any other ideas for treatment. She was told to come back if in future she wanted to get pregnant.

Dr Gunter said this is a vulnerable patient group that may struggle with feelings of helplessness without access to treatment. She said misinformation often caused patients to delay seeking medical help, and that this could lead to the development of further conditions, such as type 2 diabetes.

In Nigeria, Medlyn, a medical student, is trying to tackle some of the shame surrounding PCOS. After trying diets and supplements to no avail, she now encourages other women to consult with their doctors and embrace evidence-based treatment.

“When you’re diagnosed with PCOS it comes with so much stigma. People think you’re lazy, you don’t look after yourself, that we can’t get pregnant,” she said. “So nobody wants to date you, nobody wants to marry you.”

But she is now embracing some of her PCOS features. “It’s been a hard journey to accept my PCOS, my hair, my weight,” she said. “These things make me different.”

Sasha Ottey of the US-based charity PCOS Challenge said medical treatment usually enables people with the condition to get pregnant.

“Women with PCOS have the same number of children as those without,” she said. “You just might need a bit of help getting there.”

Dr Gunter said that women who aren’t getting help from a general practitioner should ask to see a specialist.

“Some women need a trusted endocrinologist or a trusted obstetrics and gynaecology specialist for that next level of management.”

Sophie and her doctors are still trying out possible treatments, looking for one that works for her.